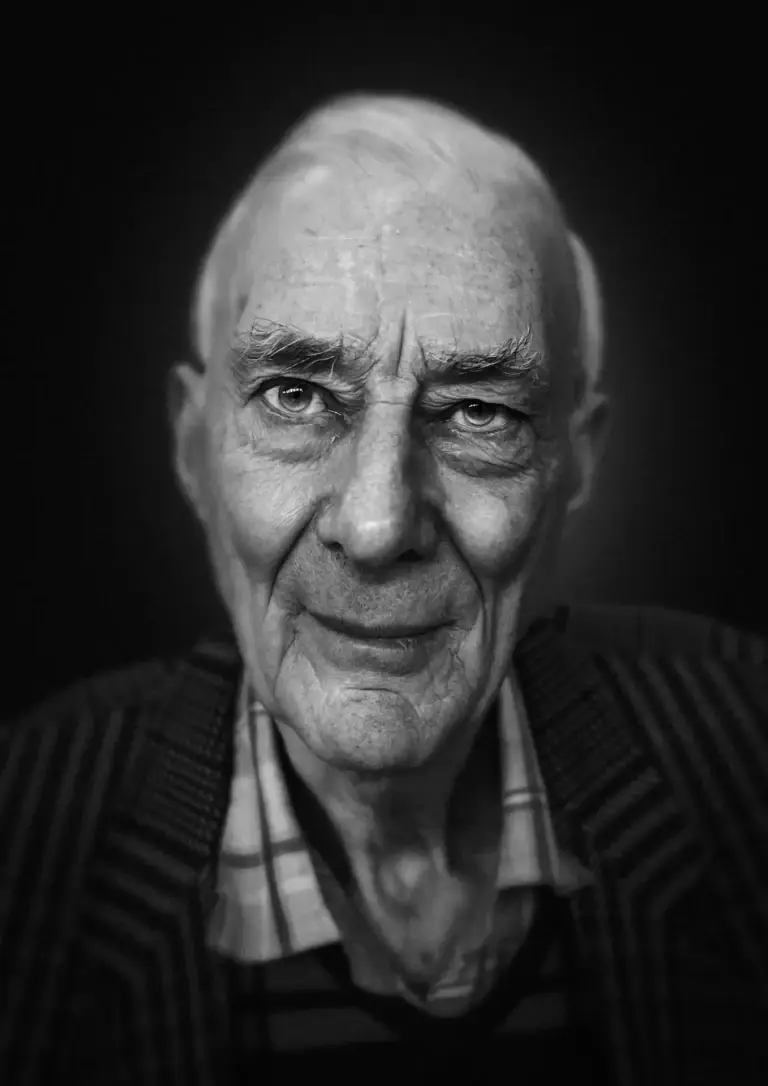

That’s my husband. Yeah. He’s got dementia.

Before the diagnosis, on a superficial level, we were quite chatty. We were both involved in each other’s lives. I’d talk to him about trivial things like, “Shall I cook this or that for dinner?” and he’d say, “Why don’t you do so-and-so?” That relationship has completely gone now. He can’t make decisions, and I’ve realised I have to make them all for him.

We used to just chat about day-to-day things. If one of the grandchildren did something funny or got ill, I’d tell him and he’d be interested. He used to paint—loved it, really. It was his hobby, and he was actually quite talented. If one of the children had chickenpox or something, he’d draw a funny cartoon and we’d post it to them. There was always this level of friendship and amusement between us. But now… the humour’s gone. Completely. Even if I make a really silly joke, there’s just no smile. It’s like it’s all faded.

These days, the relationship feels childlike. It’s like being with a three- or four-year-old. You have to explain everything very carefully. Like, washing your hands—“Turn the tap on. Make your hands wet. Take some soap. That’s right. Rub your hands together. Don’t forget the backs.” You get the picture. That’s what it’s like now.

Painting was his love. It was his life. We had this little wooden chalet in the garden. He’d fitted it with lighting and power, and that was his art studio. As soon as he’d finished dinner, he’d be out there. Sometimes early in the morning too, until late at night. He painted transport—really detailed things. Aeroplanes, ships, trains, motorbikes—you name it. Friends used to ask him, “Al, can you paint my motorbike for me?” They weren’t big commissions, not financially, but he poured everything into them.

He did this whole book on rigging when he was painting galleons. So much research. And his work—it was almost draftsman-like. He could copy any style. Sometimes impressionist, sometimes hyper-real. People would see his paintings and say, “Oh, is that the photo for your next piece?” and he’d say, “No, that is the painting.”

He was actually a printer, worked in Fleet Street for years before moving to the Isle of Dogs. But painting—that was who he was.

He had a real connection with the children. Always playing with them, making things, inventing little contraptions to amuse them. It was lovely.

Looking back, I think I saw signs a long time ago. Probably 20 years. I remember Becky, one of my daughters—she’s in her mid-40s now—she was about nine at the time. They were driving to Norfolk, and he got completely lost. We’d written out the route in detail—this was before satnavs and smartphones—and he just couldn’t relate what was written to what he was doing. Becky told me afterwards that she ended up directing the whole journey. She was nine! “Take the A231, next left,” and so on. I didn’t think much of it then. But looking back, that was probably the first sign.

In 2017, I tried to get a diagnosis, and it was a bit of a disaster. I knew he had dementia by then. It was so obvious. The GP referred us to the NHS, and we ended up with this nurse at the dementia clinic in Stourport. She wasn’t a specialist—just someone running the tests.

One of them was to copy this complex 3D diagram—three interlocked cubes—and he drew it perfectly, quickly. She looked surprised and said, “Someone who can draw like that doesn’t have dementia.” And I just thought, “You silly woman.” Because drawing and painting—that’s in his bones. That’s all he did. She didn’t get it. And I didn’t push further at that time.

Then in 2022, I insisted on a proper diagnosis. He was finally diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. Can’t remember his exact score, but it clearly showed it. Not catastrophic, but nowhere near normal.

Since then? Well… everything’s changed. I’m living with a child, basically. He can’t make decisions, not even small ones. “Do you want rice or pasta?” “I don’t know.” Push him a bit—still, “I don’t know.” Eventually, “You decide.” I realised it’s not fair even asking. Same with eggs—scrambled or poached? It’s too much. The thinking required just isn’t there anymore.

We don’t have conversations now. Not even about what’s on TV or in the news. There’s no back and forth. It’s silent companionship, really.

And I think the hardest thing, for me, is the loneliness. He doesn’t realise he has dementia. I’ve told him—“You’ve got dementia”—but he doesn’t understand what that means. He thinks he can still do things. But then he’ll nod off with a cup of tea in his hand and spill it all over the carpet. I’ve learned to spot it now—take the cup away quietly before it happens.

His spatial awareness is terrible now. He bumps into things, treads on my feet, falls over. We joke—no dancing for us. But really, it’s not funny. It’s just what it is.

I’ve been lucky in some ways. I’ve got good friends, and they’re very kind. They accept he won’t really join in a conversation when we’re out. Some treat him like a child, gently. One of my close friends, Judy, invited him to her allotment to help dig up some old currant bushes. She gave clear instructions, and he did a brilliant job. He came back happy—physically tired, but proud. That’s the sort of thing that works: familiar tasks, clear steps, kindness.

The hard bit is that most people don’t see the dementia. He’s polite. Socially responsive. “How are you?” “I’m good, how are you?” It fools people. But then if the conversation goes deeper, he just blanks. And I have to step in and say, “He’s got dementia.” That helps people make sense of the gaps.

He remembers the past in perfect detail. Tell him something about Fleet Street or the Isle of Dogs, and he’ll go on for ages. It’s all word-perfect. But ask him what he did this morning, and he’s lost. Tell him to put something in the bin, and it ends up on the coffee table. He doesn’t remember leaving it there.

My daughters—they’ve accepted it completely. They saw their grandfather go through this, so it’s not new to them. They’re wonderful.

But yes, there are moments. He has a sweet tooth, and if there’s fruitcake on the table, he’ll just help himself—again and again. At buffets, if I don’t keep an eye on him, he’ll overeat or drink too much. Then he’ll be sick—sometimes all over the carpet. I’ve had late nights cleaning up after those.

So I’m more careful now. At home, I’ll plate up food for him. At family gatherings, they’ll water down wine with lemonade. He doesn’t notice. Taste has changed too.

When I’ve got time, we do activities. Even simple things, like making coleslaw—grating carrots, chopping apples. I get him involved, step by step. He focuses. It calms him. We’ve even tried painting again. I’ll give him a little cartoon image, small canvas, acrylics. He enjoys it, even if it’s nothing like the paintings he used to do. It’s something. It’s still there, a little spark.

I also keep busy. I’m a director of the park homes where we live. I help run the village hall. I run a monthly group called Young at Heart. I go to Art Salad, a brilliant local art group. These things help me cope. They keep me grounded.

One of the most important things I’ve learned is to give him warning. Like with a toddler, you have to prepare him. “In twenty minutes, we’re leaving. You’ll need your shoes.” Then ten-minute warning. Five-minute warning. If I don’t do that and just spring things on him, we get shouting. Panic. It’s not fair on either of us.

Same with driving. He used to get so angry, convinced I was going the wrong way. Now, I talk through the route as we go—“We’re turning off soon… look, I’m indicating now.” And he’s fine.

I’ve even noticed similarities to autism. I’ve got two grandchildren on the spectrum—one non-verbal—and there’s definitely a link in how routine and preparation make such a difference. It’s all the brain, isn’t it?

I’ve made lists of services, groups, activities. Passed them to our social prescriber. I hope she uses them. I’ve been lucky enough to know how to look things up, find what’s out there. A lot of carers don’t have the time, the energy, or the headspace.

There are some wonderful groups around here—Art Salad, the lunch club in London Colney, groups for exercise and coffee. We talk. We support each other. When our husbands are driving us up the wall, we have someone to ring.

As for the future… well, I don’t go there. I saw what dementia did to my father. The last year—he couldn’t walk, couldn’t swallow. It was cruel. That might be ahead of me. Or maybe not. I don’t know. Nobody does.

If he becomes doubly incontinent, I don’t think I’ll be able to cope. But we’re not there yet. We do our activities. We manage. Day by day.

If there’s one bit of advice I’d give to someone in the early stages—it’s this: Do what you can, while you can. Take it one day at a time. Don’t try and recreate the past or expect things to stay the same. Keep your days simple. A coffee. A slice of cake. That’s enough. That’s more than enough.

And just respond—without overthinking—to what’s in front of you. That’s how you love someone with dementia. That’s how you cope.